Corruptions and Breach of the Refuge

Corruptions of the refuge are factors that make the going for refuge impure, insincere, and ineffective. According to the commentaries there are three factors that defile the going for refuge — ignorance, doubt, and wrong views. If one does not understand the reasons for going for refuge, the meaning of taking refuge, or the qualities of the refuge-objects, this lack of understanding is a form of ignorance which corrupts the going for refuge. Doubt corrupts the refuge insofar as the person overcome by doubt cannot settle confidence firmly in the Triple Gem. His commitment to the refuge is tainted by inner perplexity, suspicion, and indecision. The defilement of wrong views means a wrong understanding of the act of refuge or the refuge-objects. A person holding wrong views goes for refuge with the thought that the refuge act is a sufficient guarantee of deliverance; or he believes that the Buddha is a god with the power to save him, or that the Dhamma teaches the existence of an eternal self, or that the Sangha functions as an intercessory body with the ability to mediate his salvation. Even though the refuge act is defiled by these corruptions, as long as a person regards the Triple Gem as his supreme reliance his going for refuge is intact and he remains a Buddhist follower. But though the refuge is intact, his attitude of taking refuge is defective and has to be purified. Such purification can come about if he meets a proper teacher to give him instruction and help him overcome his ignorance, doubts, and wrong views.

The breach of the refuge means the breaking or violation of the commitment to the threefold refuge. A breach of the refuge occurs when a person who has gone for refuge comes to regard some counterpart to the three refuges as his guiding ideal or supreme reliance. If he comes to regard another spiritual teacher as superior to the Buddha, or as possessing greater spiritual authority than the Buddha, then his going for refuge to the Buddha is broken. If he comes to regard another religious teaching as superior to the Dhamma, or resorts to some other system of practice as his means to deliverance, then his going for refuge to the Dhamma is broken. If he comes to regard some spiritual community other than the ariyan Sangha as endowed with supramundane status, or as occupying a higher spiritual level than the ariyan Sangha, then his going for refuge to the Sangha is broken. In order for the refuge-act to remain valid and intact, the Triple Gem must be recognized as the exclusive resort for ultimate deliverance: “For me there is no other refuge, the Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha are my supreme refuge.”[4]

Breaking the commitment to any of the three refuge-objects breaks the commitment to all of them, since the effectiveness of the refuge-act requires the recognition of the interdependence and inseparability of the three. Thus by adopting an attitude which bestows the status of a supreme reliance upon anything outside the Triple Gem, one cuts off the going for refuge and relinquishes one’s claim to be a disciple of the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha.[5] In order to become valid once again the going for refuge must be renewed, preferably by confessing one’s lapse and then by once more going through the entire formal ceremony of taking refuge.

The Similes for the Refuges

In the traditional Indian method of exposition no account or treatment of a theme is considered complete unless it has been illustrated by similes. Therefore we conclude this explanation of going for refuge with a look at some of the classical similes for the objects of refuge. Though many beautiful similes are given in the texts, from fear of prolixity we here limit ourselves to four.

The first simile compares the Buddha to the sun, for his appearance in the world is like the sun rising over the horizon. His teaching of the true Dhamma is like the net of the sun’s rays spreading out over the earth, dispelling the darkness and cold of the night, giving warmth and light to all beings. The Sangha is like the beings for whom the darkness of night has been dispelled, who go about their affairs enjoying the warmth and radiance of the sun.

The second simile compares the Buddha to the full moon, the jewel of the night-time sky. His teaching of the Dhamma is like the moon shedding its beams of light over the world, cooling off the heat of the day. The Sangha is like the persons who go out in the night to see and enjoy the refreshing splendor of the moonlight.

In the third simile the Buddha is likened to a great raincloud spreading out across the countryside at a time when the land has been parched with a long summer’s heat. The teaching of the true Dhamma is like the downpour of the rain, which inundates the land giving water to the plants and vegetation. The Sangha is like the plants — the trees, shrubs, bushes, and grass — which thrive and flourish when nourished by the rain pouring down from the cloud.

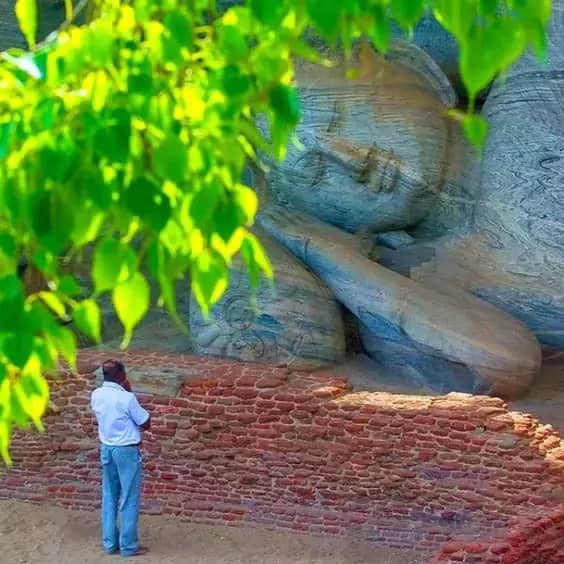

The fourth simile compares the Buddha to a lotus flower, the paragon of beauty and purity. Just as a lotus grows up in a muddy lake, but rises above the water and stands in full splendor unsoiled by the mud, so the Buddha, having grown up in the world, overcomes the world and abides in its midst untainted by its impurities. The Buddha’s teaching of the true Dhamma is like the sweet perfumed fragrance emitted by the lotus flower, giving delight to all. And the Sangha is like the host of bees who collect around the lotus, gather up the pollen, and fly off to their hives to transform it into honey.

Read Next

Source : “Going for Refuge & Taking the Precepts”, by Bhikkhu Bodhi. Access to Insight (BCBS Edition), 1 December 2013, http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/bodhi/wheel282.html .